The good, the bad and the ugly is the simple way to sum up Cambodian history. Things were good in the early years, culminating in the vast Angkor empire, unrivalled in the region during four centuries of dominance. Then the bad set in, from the 13th century, as ascendant neighbors steadily chipped away at Cambodian territory. In the 20th century it turned downright ugly, as a brutal civil war lead to the genocidal rule of the Khmer Rouge (1975 – 1979), from which Cambodia is still recovering.

Early:

Cambodia came into being, so the story goes, through the union of a princess and a foreigner. The foreigner was an Indian Brahman named Kaundinya and the princess was the daughter of a dragon king who ruled over a watery land. One day, as Kaundinya sailed by the princess paddled out in a boat to greet him. Kaundinya shot and arrow from his magic bow into her boat, causing the fearful princess to agree to marriage. In need of a dowry, her father drank up the waters of his land and presented them to Kaundinya to rule over. The new kingdom was named Kambuja.

Like many legends, this one is historically opaque, but it does say something about the cultural forces that brought Cambodia into existence; in particular its relationship with its great sub continental neighbors, India. Cambodia’s religious, royal and written traditions stemmed from India and began to coalesce as a cultural entity in their own right between the 1st and 5 th centuries.

Very little is known about prehistoric Cambodia. Much of the southeast was a vast, shallow gulf that was progressively silted up by the mouths of the Mekong, leaving pancake-flat, mineral-rich land ideal for farming. Evidence of cave-dwellers has been found in the northwest of Cambodia. Carbon dating on ceramic pots found in the area shows that they were made around 4200BC, but it is hard to say whether there is a direct relationship between these cave-dwelling pot makers and contemporary Khmers. Examinations of bones dating back to around 1500 BC, however, suggest that the people living in Cambodia at that time resembled the Cambodians of today. Early Chinese records report that the Cambodians were 'ugly' and 'dark' and went about naked; but a pinch of salt is always required when reading the culturally chauvinistic reports of imperial China concerning its ‘barbarian’ neighbors.

Indianisation and Funan:

The early Indianisation of Cambodia occurred via trading settlements that sprang up from the 1st century on the coastline of what is now southern Vietnam, but was then inhabited by Cambodians. These settlements were ports of call for boats following the trading route from the Bay of Bengal to the southern provinces of China. The largest of these nascent kingdoms was known as Funan by the Chinese, and may have existed across an area between Ba Phnom in Prey Veng Province, a site only worth visiting for the archaeologically obsessed today, and Oc-Eo in Kien Giang Province in southern Vietnam. It would have been a contemporary of Champasak in southern Laos (then known as Kuruksetra) and other lesser fiefdoms in the region.

Funan is a Chinese name, and it may be a transliteration of the ancient Khmer word bnam (mountain). Although very little is known about Funan, much has been made of its importance as an early Southeast Asian centre of power.

It is most likely that between the 1st and 8th centuries, Cambodia was a collection of small states, each with its won elites that often strategically intermarried and often went to war with one another. Funan was no doubt one of these states, and as a major sea port would have been pivotal in the transmission of Indian culture into the interior of Cambodia.

What historians do know about Funan they have mostly gleaned from Chinese sources. These report that Funan-period Cambodia (1st to 6th centuries AD) embraced the worship of the Hindu deities Shiva and Vishnu and, at the same time, Buddhism. The linga (phallic totem) appears to have been the focus of ritual and an emblem of kingly might, a feature that was to evolve further in the Angkorian cult of the god-king. The people practiced primitive irrigation, which enabled the cultivation of rice, and traded raw commodities such as spices with China and India.

Chenla Period:

From the 6th century the Funan kingdom’s importance as a port of call declined, and Cambodia’s population gradually concentrated along the Mekong and Tonlé Sap Rivers, where the majority remains today. The move may have been related to the development of we-rice agriculture. From the 6th to 8th centuries it was likely that Cambodia was a collection of competing kingdoms, ruled by autocratic kings who legitimized their absolute rule through hierarchical caste concepts borrowed from India.

This era is generally referred to as the Chenla period. Again, like Funan, it is a Chinese term and there is little to support the idea that the Chenla was a unified kingdom that held sway over all of Cambodia. Indeed, the Chinese themselves referred to ‘water Chenla’ and ‘land Chenla’. Water Chenla was located around Angkor Borei and the temple mount of Phnom Da, near the present-day provincial capital of Takeo, and land Chenla in the upper reaches of the Mekong River and east of the Tonlé Sap lake, around Sambor Prei Kuk, an essential stop on a chronological jaunt through Cambodia’s history.

The people of Cambodia were well known to the Chinese, and gradually the region was becoming more cohesive. Before long the fractured kingdoms of Cambodia would merge to become the greatest empire in Southeast Asia.

Angkor Period:

A popular place of pilgrimage for Khmers today, the sacred mountain of Phnom Kulen, to the northeast of Angkor, is home to an inscription that tells us in 802 Jayavarman II proclaimed himself a ‘universal monarch’, or devaraja (god-king). It is believed that he may have resided in the Buddhist Shailendras’court in Java and a young man. One of the first things he did when he returned to Cambodia was to reject Javanese control over the southern lands of Cambodia. Jayavarman II then set out to bring the country under his control through alliances and conquests, the first monarch to rule and of what we call Cambodia today.

Jayavarman II was the first of a long succession of kings who presided over the rise and fall of the Southeast Asian empire that was to leave the stunning legacy of Angkor. The first records of the massive irrigation works that supported the population of Angkor date to the reign of Indravarman I (877-89). His rule also marks the beginning of Angkorian art, with the building of temples in the Roluos area, notably the Bakong. His son Yasovarman I (889-910) moved the royal court to Angkor proper, establishing a temple-mountain on the summit of Phnom Bakheng.

By the turn of the 11th century the kingdom of Angkor was losing control of its territories. Suryavarman I (1002-49), a usurper, moved into the power vacuum and, like Javavarman II two centuries before, reunified the kingdom through war and alliances. He annexed the Dravati kingdom of Lopburi in Thailand and widened his control of Cambodia, stretching the empire to perhaps its greatest extent. A pattern was beginning to emerge, and can be seen throughout the Angkorian period: dislocation and turmoil, followed by reunification and further expansion under a powerful king. Architecturally, the most productive periods occurred after times of turmoil, indicating that newly incumbent monarchs felt the need to celebrate and perhaps legitimize their rule with massive building projects.

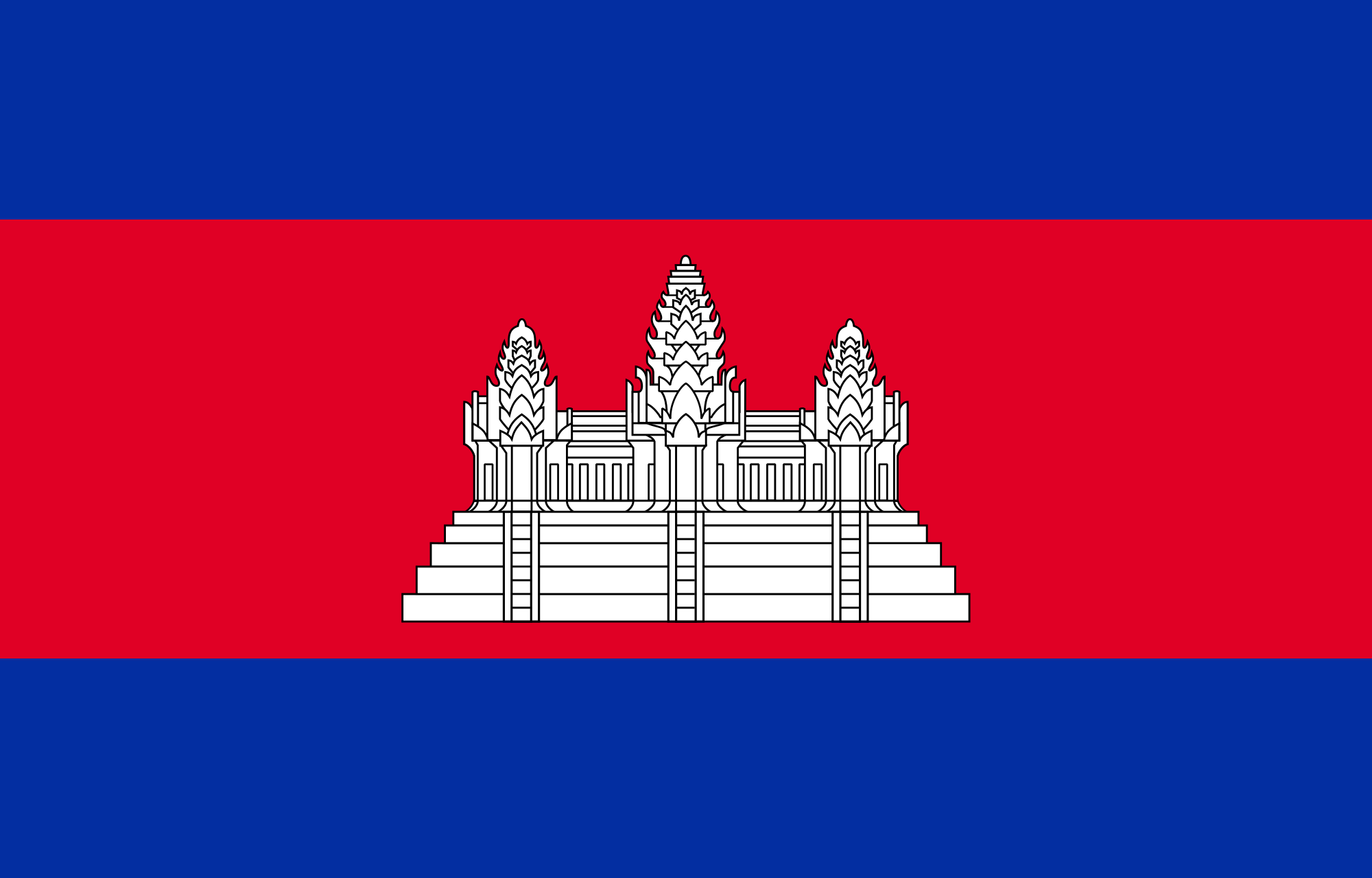

By 1066 Angkor was again riven by conflict, becoming the focus of rival bids for power. It was not until the accession of Suryavarman II (in 1112) that the kingdom was again unified. Suryavarman II embarked on another phase of expansion, waging wars in Vietnam and the region of central Vietnam known as Champa. He also established links with China. But Suryavarman II is immortalized as the king who, in his devotion to the Hindu deity Vishnu, commissioned the majestic temple of Angkor Wat.

Suryavarman II had brought Champa to heel and reduced it to vassal status. In 1177, however, the Chams struck back with a naval expedition up the Mekong and into Tonlé Sap Lake. They took the city of Angkor by surprise and put King Dharanindravarman II to death. The next year a cousin of Suryavarman II gathered forces and defeated the Chams in another naval battle. The new leader was crowned Jayavarman VII in 1181.

A devout follower of Mahayana Buddhism, Jayavarman VII built the city of Angkor Thom and many other massive monuments. Indeed, many of the monuments visited by tourists around Angkor today were constructed during Jayavarman VII’s reign. However, Jayavarman VII is a figure of many contradictions. The bas-reliefs of the Bayon depict him presiding over battles of terrible ferocity, while statues of the king show him in a meditative, otherworldly aspect. His program of temple construction and other public works was carried out in great haste, no doubt bringing enormous hardship to the laborers who provided the muscle, and thus accelerating the decline of the empire. He was partly driven by a desire to legitimize his rule, as there may have been other contenders closer to the royal bloodline, and partly by the need to introduce a new religion to a population predominantly Hindu in faith.

Decline and Fall:

Some scholars maintain that decline was hovering in the wings at the time Angkor Wat was built, when the Angkorian empire was at the height of its remarkable productivity. There are indications that the irrigation network was overworked and slowly starting to silt up due to the massive deforestations that had taken place in the heavily populated areas to the north and east of Angkor. Massive construction projects such as Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom no doubt put an enormous strain on the royal coffers and on thousands of slaves and common people who subsidized them in hard work and taxes. Following the reign of Jayavarman VII, temple construction effectively ground to a halt, in large part because Jayavarman VII’s public works quarried local sandstone into oblivion and the population was exhausted.

Another important aspect of this period was the decline of Cambodian political influence on the peripheries of its empire. At the same time, the Thais were ascendant, having migrated south from Yunnan to escape Kublai Khan and his Mongol hordes. The Thais, first from Sukothai, later Ayuthaya, grew in strength and made repeated incursions into Angkor, finally sacking the city in 1431 and making off with thousands of intellectuals, artisans and dancers from the royal court. During this period, perhaps drawn by the opportunities for sea trade with China and fearful of the increasingly bellicose Thais, the Khmer elite began to migrate to the Phnom Penh area. The capital shifted several times in the 16th century but eventually settled in present day Phnom Penh.

The Dark Ages:

From 1600 until the arrival of the French in 1863, Cambodia was ruled by a series of weak kings who, because of continual challenges by dissident members of the royal family, were forced to seek the protection-granted, of course, at a price-of either Thailand or Vietnam. In the 17th century, assistance from the Nguyen lords of southern Vietnam was given on the proviso that Vietnamese be allowed to settle in what is now the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam, at that time part of Cambodia and today still referred to by the Khmers as Kampuchea Krom (Lower Cambodia).

In the west, the Thais controlled the provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap from 1794; by the late 18th century they had firm control of the Cambodian royal family. Indeed, one king was crowned in Bangkok and placed on the throne at Udong with the help of the Thai army. That Cambodia survived through the 18th century as a distinct entity is due to the preoccupations of its neighbors: while the Thais were expending their energy and resources in fighting the Burmese, the Vietnamese were wholly absorbed by internal strife.

French Rule:

Cambodia’s long period of bouncing back and forth between Thai and Vietnamese masters ended in 1864, when French gunboats intimidated King Norodom I (1860-1904) into signing a treaty of protectorate. French control of Cambodia, which developed as a sideshow to French-colonial interests in Vietnam, initially involved little direct interference in Cambodia’s affairs. More importantly, the French presence prevented Cambodia’s expansionist neighbors from annexing any more Khmer territory and helped keep Norodom on the throne despite the ambitions of his rebellious half-brothers.

By the 1870s French officials in Cambodia began pressing for greater control over internal affairs. In 1884, Norodom was forced into signing a treaty that turned his country into a virtual colony. This sparked a two-year rebellion that constituted the only major anti-French movement in Cambodia until after WWII. This uprising ended when the king was persuaded to call upon the rebel fighters to lay down their weapons in exchange for a return to the pre-treaty arrangement.

During the next two decades senior Cambodian officials, who saw certain advantages in acquiescing to French power, opened the door to direct French control over the day-today administration of the country. At the same time the French maintained Norodom’s court in a splendor unseen since the heyday of Angkor, thereby greatly enhancing the symbolic position of the monarchy. The French were able to pressure Thailand into returning the northwest provinces of Battambang, Siem Reap and Sisophon in 1907, in return for concessions of Lao territory to the Thais, returning Angkor to Cambodian control for the first time in more than a century.

King Norodom I was succeeded by King Sisowath (1904-27), who was succeeded by King Monivong (1927-41). Upon King Monivong’s death, the French governor general of Japanese-occupied Indochina, Admiral Jean Decoux, placed 19-year-old Prince Norodom Sihanouk on the Cambodian throne. Sihanouk would prove pliable, so the assumption went, but this proved to be a major miscalculation.

During WWII, Japanese forces occupied much of Asia, and Cambodia was no exception. However, with many in France collaboration with the occupying Germans, the Japanese were happy to let these French allies control affairs in Cambodia. The price was conceding to Thailand (a Japanese ally of sorts) much of Battambang and Siem Reap Provinces once again, areas that weren’t returned until 1947. However, with the fall of Paris in 1944 and French policy in disarray, the Japanese were forced to take direct control of the territory by early 1945. After WWII, the French returned, making Cambodia an autonomous state within the French Union, but retaining de facto control. The French deserved independence it seemed, but not its colonies. The immediate postwar years were marked by strife among the country’s various political factions, a situation made more unstable by the Franco-Viet Minh War then raging in Vietnam and Laos, which spilled over into Cambodia. The Vietnamese, as they were also to do 20 years later in the war against Lon Nol and the Americans, trained and fought with bands of Khmer Issarak (Free Khmer) against the French authorities.

Modern History

By 1953 a strong local leader, King Sihanouk, had risen to power with the Khmer and sought independence for his country. King Sihanouk was a masterful politician and succeeded in wringing form the French the independence of Cambodia. King Sihanouk also established the People’s Socialist Communist Party at this time. After abdicating the throne to pursue a political career, Sihanouk became the country’s first prime minister. He managed to keep Cambodia neutral in the Vietnam War until 1965, when he broke with the United States and allowed North Vietnam and the Vietcong to use Cambodian territory. This led to the bombing of Cambodia by United States forces.

Sihanouk was deposed by one of his generals in 1970 and fled the country to China, where he set up a government in exile that supported the Cambodian revolutionary movement known as the Khmer Rouge. Meanwhile, in Cambodia, United States and South Vietnamese forces invaded the country in an attempt to eliminate Vietcong forces hiding there. For the next five years, as savage fighting spread throughout Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge gained land and power. In 1975 the capital at Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge, and their leader, Pol Pot, became the leader of Cambodia.

What followed for the next three years remains one of the most horrific incidents in world history. The Khmer Rouge forced the entire population of Phnom Penh and other cities to evacuate to the countryside where they were placed in slave labor units and forced to do manual work until they dropped from exhaustion. Pol Pot and his followers began a campaign of systematic genocide against their own people, with the aim of returning Cambodia to the agrarian society of centuries before. Great segments of the population were slaughtered senselessly. People with any type of education, those who wore glasses or were doctors and nurses, anybody who had worked at a bank—these people were all mindlessly killed. Banks were blown up, airports closed, and money was abolished. The horror of the Pol Pot regime went unnoticed for several years.

Finally in 1978, Vietnam, which had been watching the persecution and death of its own citizens trapped in Cambodia, liberated Cambodia and chased Pol Pot and his followers out of the cities and back into the remote mountains. By 1979, Pol Pot had been ousted and the Vietnamese installed a new government. Until 1990 civil war continued sporadically in Cambodia, but gradually the murderous followers of Pol Pot were eliminated from power. Pol Pot died under house arrest in 1998.

Throughout the 1990’s United Nations peacekeeping efforts helped stabilize the country. By 1997, a government amnesty convinced most Khmer Rouge partisans to cease fighting, and on October 4, 2004 the Cambodian National Assembly agreed with the U.N. to set up an international war crimes tribunal to try senior Khmer Rouge officials for the genocide of the 1970s. The first trial began in 2009 against the former head of S-21 prison; more leaders are expected to be tried over the next decade.

Another stabilizing influence during recent decades has been the return of the monarchy in 1993, when King Sihanouk was restored to the throne. In 2004, ill health forced him to abdicate in favor of his son, Norodom Sihamoni, who currently reigns as a constitutional monarchy.

Cambodia came into being, so the story goes, through the union of a princess and a foreigner. The foreigner was an Indian Brahman named Kaundinya and the princess was the daughter of a dragon king who ruled over a watery land. One day, as Kaundinya sailed by the princess paddled out in a boat to greet him. Kaundinya shot and arrow from his magic bow into her boat, causing the fearful princess to agree to marriage. In need of a dowry, her father drank up the waters of his land and presented them to Kaundinya to rule over. The new kingdom was named Kambuja.

Like many legends, this one is historically opaque, but it does say something about the cultural forces that brought Cambodia into existence; in particular its relationship with its great sub continental neighbors, India. Cambodia’s religious, royal and written traditions stemmed from India and began to coalesce as a cultural entity in their own right between the 1st and 5 th centuries.

Very little is known about prehistoric Cambodia. Much of the southeast was a vast, shallow gulf that was progressively silted up by the mouths of the Mekong, leaving pancake-flat, mineral-rich land ideal for farming. Evidence of cave-dwellers has been found in the northwest of Cambodia. Carbon dating on ceramic pots found in the area shows that they were made around 4200BC, but it is hard to say whether there is a direct relationship between these cave-dwelling pot makers and contemporary Khmers. Examinations of bones dating back to around 1500 BC, however, suggest that the people living in Cambodia at that time resembled the Cambodians of today. Early Chinese records report that the Cambodians were 'ugly' and 'dark' and went about naked; but a pinch of salt is always required when reading the culturally chauvinistic reports of imperial China concerning its ‘barbarian’ neighbors.

Indianisation and Funan:

The early Indianisation of Cambodia occurred via trading settlements that sprang up from the 1st century on the coastline of what is now southern Vietnam, but was then inhabited by Cambodians. These settlements were ports of call for boats following the trading route from the Bay of Bengal to the southern provinces of China. The largest of these nascent kingdoms was known as Funan by the Chinese, and may have existed across an area between Ba Phnom in Prey Veng Province, a site only worth visiting for the archaeologically obsessed today, and Oc-Eo in Kien Giang Province in southern Vietnam. It would have been a contemporary of Champasak in southern Laos (then known as Kuruksetra) and other lesser fiefdoms in the region.

Funan is a Chinese name, and it may be a transliteration of the ancient Khmer word bnam (mountain). Although very little is known about Funan, much has been made of its importance as an early Southeast Asian centre of power.

It is most likely that between the 1st and 8th centuries, Cambodia was a collection of small states, each with its won elites that often strategically intermarried and often went to war with one another. Funan was no doubt one of these states, and as a major sea port would have been pivotal in the transmission of Indian culture into the interior of Cambodia.

What historians do know about Funan they have mostly gleaned from Chinese sources. These report that Funan-period Cambodia (1st to 6th centuries AD) embraced the worship of the Hindu deities Shiva and Vishnu and, at the same time, Buddhism. The linga (phallic totem) appears to have been the focus of ritual and an emblem of kingly might, a feature that was to evolve further in the Angkorian cult of the god-king. The people practiced primitive irrigation, which enabled the cultivation of rice, and traded raw commodities such as spices with China and India.

Chenla Period:

From the 6th century the Funan kingdom’s importance as a port of call declined, and Cambodia’s population gradually concentrated along the Mekong and Tonlé Sap Rivers, where the majority remains today. The move may have been related to the development of we-rice agriculture. From the 6th to 8th centuries it was likely that Cambodia was a collection of competing kingdoms, ruled by autocratic kings who legitimized their absolute rule through hierarchical caste concepts borrowed from India.

This era is generally referred to as the Chenla period. Again, like Funan, it is a Chinese term and there is little to support the idea that the Chenla was a unified kingdom that held sway over all of Cambodia. Indeed, the Chinese themselves referred to ‘water Chenla’ and ‘land Chenla’. Water Chenla was located around Angkor Borei and the temple mount of Phnom Da, near the present-day provincial capital of Takeo, and land Chenla in the upper reaches of the Mekong River and east of the Tonlé Sap lake, around Sambor Prei Kuk, an essential stop on a chronological jaunt through Cambodia’s history.

The people of Cambodia were well known to the Chinese, and gradually the region was becoming more cohesive. Before long the fractured kingdoms of Cambodia would merge to become the greatest empire in Southeast Asia.

Angkor Period:

A popular place of pilgrimage for Khmers today, the sacred mountain of Phnom Kulen, to the northeast of Angkor, is home to an inscription that tells us in 802 Jayavarman II proclaimed himself a ‘universal monarch’, or devaraja (god-king). It is believed that he may have resided in the Buddhist Shailendras’court in Java and a young man. One of the first things he did when he returned to Cambodia was to reject Javanese control over the southern lands of Cambodia. Jayavarman II then set out to bring the country under his control through alliances and conquests, the first monarch to rule and of what we call Cambodia today.

Jayavarman II was the first of a long succession of kings who presided over the rise and fall of the Southeast Asian empire that was to leave the stunning legacy of Angkor. The first records of the massive irrigation works that supported the population of Angkor date to the reign of Indravarman I (877-89). His rule also marks the beginning of Angkorian art, with the building of temples in the Roluos area, notably the Bakong. His son Yasovarman I (889-910) moved the royal court to Angkor proper, establishing a temple-mountain on the summit of Phnom Bakheng.

By the turn of the 11th century the kingdom of Angkor was losing control of its territories. Suryavarman I (1002-49), a usurper, moved into the power vacuum and, like Javavarman II two centuries before, reunified the kingdom through war and alliances. He annexed the Dravati kingdom of Lopburi in Thailand and widened his control of Cambodia, stretching the empire to perhaps its greatest extent. A pattern was beginning to emerge, and can be seen throughout the Angkorian period: dislocation and turmoil, followed by reunification and further expansion under a powerful king. Architecturally, the most productive periods occurred after times of turmoil, indicating that newly incumbent monarchs felt the need to celebrate and perhaps legitimize their rule with massive building projects.

By 1066 Angkor was again riven by conflict, becoming the focus of rival bids for power. It was not until the accession of Suryavarman II (in 1112) that the kingdom was again unified. Suryavarman II embarked on another phase of expansion, waging wars in Vietnam and the region of central Vietnam known as Champa. He also established links with China. But Suryavarman II is immortalized as the king who, in his devotion to the Hindu deity Vishnu, commissioned the majestic temple of Angkor Wat.

Suryavarman II had brought Champa to heel and reduced it to vassal status. In 1177, however, the Chams struck back with a naval expedition up the Mekong and into Tonlé Sap Lake. They took the city of Angkor by surprise and put King Dharanindravarman II to death. The next year a cousin of Suryavarman II gathered forces and defeated the Chams in another naval battle. The new leader was crowned Jayavarman VII in 1181.

A devout follower of Mahayana Buddhism, Jayavarman VII built the city of Angkor Thom and many other massive monuments. Indeed, many of the monuments visited by tourists around Angkor today were constructed during Jayavarman VII’s reign. However, Jayavarman VII is a figure of many contradictions. The bas-reliefs of the Bayon depict him presiding over battles of terrible ferocity, while statues of the king show him in a meditative, otherworldly aspect. His program of temple construction and other public works was carried out in great haste, no doubt bringing enormous hardship to the laborers who provided the muscle, and thus accelerating the decline of the empire. He was partly driven by a desire to legitimize his rule, as there may have been other contenders closer to the royal bloodline, and partly by the need to introduce a new religion to a population predominantly Hindu in faith.

Decline and Fall:

Some scholars maintain that decline was hovering in the wings at the time Angkor Wat was built, when the Angkorian empire was at the height of its remarkable productivity. There are indications that the irrigation network was overworked and slowly starting to silt up due to the massive deforestations that had taken place in the heavily populated areas to the north and east of Angkor. Massive construction projects such as Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom no doubt put an enormous strain on the royal coffers and on thousands of slaves and common people who subsidized them in hard work and taxes. Following the reign of Jayavarman VII, temple construction effectively ground to a halt, in large part because Jayavarman VII’s public works quarried local sandstone into oblivion and the population was exhausted.

Another important aspect of this period was the decline of Cambodian political influence on the peripheries of its empire. At the same time, the Thais were ascendant, having migrated south from Yunnan to escape Kublai Khan and his Mongol hordes. The Thais, first from Sukothai, later Ayuthaya, grew in strength and made repeated incursions into Angkor, finally sacking the city in 1431 and making off with thousands of intellectuals, artisans and dancers from the royal court. During this period, perhaps drawn by the opportunities for sea trade with China and fearful of the increasingly bellicose Thais, the Khmer elite began to migrate to the Phnom Penh area. The capital shifted several times in the 16th century but eventually settled in present day Phnom Penh.

The Dark Ages:

From 1600 until the arrival of the French in 1863, Cambodia was ruled by a series of weak kings who, because of continual challenges by dissident members of the royal family, were forced to seek the protection-granted, of course, at a price-of either Thailand or Vietnam. In the 17th century, assistance from the Nguyen lords of southern Vietnam was given on the proviso that Vietnamese be allowed to settle in what is now the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam, at that time part of Cambodia and today still referred to by the Khmers as Kampuchea Krom (Lower Cambodia).

In the west, the Thais controlled the provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap from 1794; by the late 18th century they had firm control of the Cambodian royal family. Indeed, one king was crowned in Bangkok and placed on the throne at Udong with the help of the Thai army. That Cambodia survived through the 18th century as a distinct entity is due to the preoccupations of its neighbors: while the Thais were expending their energy and resources in fighting the Burmese, the Vietnamese were wholly absorbed by internal strife.

French Rule:

Cambodia’s long period of bouncing back and forth between Thai and Vietnamese masters ended in 1864, when French gunboats intimidated King Norodom I (1860-1904) into signing a treaty of protectorate. French control of Cambodia, which developed as a sideshow to French-colonial interests in Vietnam, initially involved little direct interference in Cambodia’s affairs. More importantly, the French presence prevented Cambodia’s expansionist neighbors from annexing any more Khmer territory and helped keep Norodom on the throne despite the ambitions of his rebellious half-brothers.

By the 1870s French officials in Cambodia began pressing for greater control over internal affairs. In 1884, Norodom was forced into signing a treaty that turned his country into a virtual colony. This sparked a two-year rebellion that constituted the only major anti-French movement in Cambodia until after WWII. This uprising ended when the king was persuaded to call upon the rebel fighters to lay down their weapons in exchange for a return to the pre-treaty arrangement.

During the next two decades senior Cambodian officials, who saw certain advantages in acquiescing to French power, opened the door to direct French control over the day-today administration of the country. At the same time the French maintained Norodom’s court in a splendor unseen since the heyday of Angkor, thereby greatly enhancing the symbolic position of the monarchy. The French were able to pressure Thailand into returning the northwest provinces of Battambang, Siem Reap and Sisophon in 1907, in return for concessions of Lao territory to the Thais, returning Angkor to Cambodian control for the first time in more than a century.

King Norodom I was succeeded by King Sisowath (1904-27), who was succeeded by King Monivong (1927-41). Upon King Monivong’s death, the French governor general of Japanese-occupied Indochina, Admiral Jean Decoux, placed 19-year-old Prince Norodom Sihanouk on the Cambodian throne. Sihanouk would prove pliable, so the assumption went, but this proved to be a major miscalculation.

During WWII, Japanese forces occupied much of Asia, and Cambodia was no exception. However, with many in France collaboration with the occupying Germans, the Japanese were happy to let these French allies control affairs in Cambodia. The price was conceding to Thailand (a Japanese ally of sorts) much of Battambang and Siem Reap Provinces once again, areas that weren’t returned until 1947. However, with the fall of Paris in 1944 and French policy in disarray, the Japanese were forced to take direct control of the territory by early 1945. After WWII, the French returned, making Cambodia an autonomous state within the French Union, but retaining de facto control. The French deserved independence it seemed, but not its colonies. The immediate postwar years were marked by strife among the country’s various political factions, a situation made more unstable by the Franco-Viet Minh War then raging in Vietnam and Laos, which spilled over into Cambodia. The Vietnamese, as they were also to do 20 years later in the war against Lon Nol and the Americans, trained and fought with bands of Khmer Issarak (Free Khmer) against the French authorities.

Modern History

By 1953 a strong local leader, King Sihanouk, had risen to power with the Khmer and sought independence for his country. King Sihanouk was a masterful politician and succeeded in wringing form the French the independence of Cambodia. King Sihanouk also established the People’s Socialist Communist Party at this time. After abdicating the throne to pursue a political career, Sihanouk became the country’s first prime minister. He managed to keep Cambodia neutral in the Vietnam War until 1965, when he broke with the United States and allowed North Vietnam and the Vietcong to use Cambodian territory. This led to the bombing of Cambodia by United States forces.

Sihanouk was deposed by one of his generals in 1970 and fled the country to China, where he set up a government in exile that supported the Cambodian revolutionary movement known as the Khmer Rouge. Meanwhile, in Cambodia, United States and South Vietnamese forces invaded the country in an attempt to eliminate Vietcong forces hiding there. For the next five years, as savage fighting spread throughout Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge gained land and power. In 1975 the capital at Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge, and their leader, Pol Pot, became the leader of Cambodia.

What followed for the next three years remains one of the most horrific incidents in world history. The Khmer Rouge forced the entire population of Phnom Penh and other cities to evacuate to the countryside where they were placed in slave labor units and forced to do manual work until they dropped from exhaustion. Pol Pot and his followers began a campaign of systematic genocide against their own people, with the aim of returning Cambodia to the agrarian society of centuries before. Great segments of the population were slaughtered senselessly. People with any type of education, those who wore glasses or were doctors and nurses, anybody who had worked at a bank—these people were all mindlessly killed. Banks were blown up, airports closed, and money was abolished. The horror of the Pol Pot regime went unnoticed for several years.

Finally in 1978, Vietnam, which had been watching the persecution and death of its own citizens trapped in Cambodia, liberated Cambodia and chased Pol Pot and his followers out of the cities and back into the remote mountains. By 1979, Pol Pot had been ousted and the Vietnamese installed a new government. Until 1990 civil war continued sporadically in Cambodia, but gradually the murderous followers of Pol Pot were eliminated from power. Pol Pot died under house arrest in 1998.

Throughout the 1990’s United Nations peacekeeping efforts helped stabilize the country. By 1997, a government amnesty convinced most Khmer Rouge partisans to cease fighting, and on October 4, 2004 the Cambodian National Assembly agreed with the U.N. to set up an international war crimes tribunal to try senior Khmer Rouge officials for the genocide of the 1970s. The first trial began in 2009 against the former head of S-21 prison; more leaders are expected to be tried over the next decade.

Another stabilizing influence during recent decades has been the return of the monarchy in 1993, when King Sihanouk was restored to the throne. In 2004, ill health forced him to abdicate in favor of his son, Norodom Sihamoni, who currently reigns as a constitutional monarchy.

0 comments:

Post a Comment